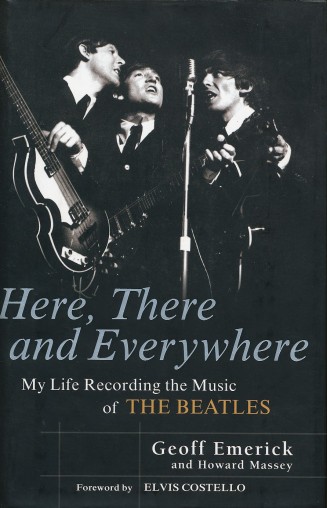

We recently purchased a nice, used hardback copy of Geoff Emerick’s fantastic Beatle book Here, There and Everywhere – My Life Recording the Music of the Beatles.

Not having read it before it’s currently our favourite, especially given the release in the last week of the The Beatles In Mono vinyl LPs as a boxed set (and also as individual albums).

Geoff Emerick was George Martin’s right-hand man in the control room at EMI’s Abbey Road studios in London. At the age of 15 (on just his second day at EMI) he was present – as an assistant recording engineer – when a scruffy-looking quartet from Liverpool came in for their very first studio session. Emerick progressed from that recording (“Love Me Do” in 1962), to being directly involved with the majority of the band’s classic albums. He confirms on a number of occasions in his book that a lot more time was spent getting the mono mixes correct as compared to the time taken over stereo.

Geoff Emerick was George Martin’s right-hand man in the control room at EMI’s Abbey Road studios in London. At the age of 15 (on just his second day at EMI) he was present – as an assistant recording engineer – when a scruffy-looking quartet from Liverpool came in for their very first studio session. Emerick progressed from that recording (“Love Me Do” in 1962), to being directly involved with the majority of the band’s classic albums. He confirms on a number of occasions in his book that a lot more time was spent getting the mono mixes correct as compared to the time taken over stereo.

With his ability to interpret the sounds that John, Paul, George and Ringo had in their heads as they worked at getting their songs down on tape, Emerick made a huge contribution to their records. He wanted as much as they did to experiment – to take the recording process into new and un-charted waters. Here, There and Everywhere takes us into the famous Studio’s One and Two at Abbey Road as history was literally being made.

Amongst other things we read about the antiquated attitudes, policies and equipment at EMI Records during the 1960s. Given their strict and old-fashioned rules it’s incredible that the greatness of the Beatles was ever captured at all. EMI management back in the day seemed stuck in the 1940s and 50s. As an organisation it frequently stood in the way of creativity rather than fostering it. It was Geoff Emerick who was willing to go out on a limb and flaunt the studio rules at Abbey Road to capture the sounds we have today.

One of the other big surprises in the book is Emerick’s low opinion of George Harrison. There are frequent mentions of how stand-offish and surly Emerick found him to be, not to mention that he regarded George as a pretty lacklustre lead guitarist….

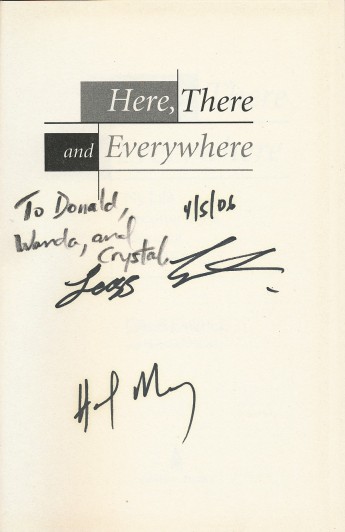

Here, There and Everywhere was published way back in 2006, but it is highly recommended if you are at all interested in the Beatles and their music. The copy we have is a signed copy. It’s not dedicated to us because this one is second-hand – but that doesn’t matter. There is the signature of Geoff Emerick (and his co-author Howard Massey), a man who had a significant impact on the Beatles legacy.

HEY JUDE DONT BE AFRAID TO TAKE A SAD SONG AND MAKE IT BETTER

LikeLike

The book, indeed a splendid read, is full of mistakes I’m afraid. It gets rather bad critics from ‘the people who were there’. To give you two examples: Emerick writes that the birds heared on ‘Blackbird’ were there because Paul recorded the song outside the studio, and at least some birdsounds are thus from the exterior of Abbey Road. Second he writes John hated O-bla-di-O-bla-da so much he refused to set foot in the studio when they were working on that song. Nót, you can hear his voice throughout the song! I recommend the Ken Scott book.

LikeLike

Hi, yes it is a splendid read. As to being “full of mistakes”, it is clearly written through the eyes of someone who was on the other side of the glass in a technician’s role – so there is that element to his observations of the band. He was there, but was an observer once removed. If you read the book in that light it remains a fascinating insight into how they matured as a band, how their music and approach to recording developed, and how ultimately they began to fall apart. Emerick clearly has various biases about the Beatles as individuals and as players and composers. He is pro Paul, anti George, and critical of Lennon’s personality and drug use. You have to take that into account. But at least Geoff Emerick was there. So when he says that ‘Blackbird’ was recorded outdoors at Abbey Road studios (see page 239), who’s to say it wasn’t? Paul did 32 takes of the song, 11 of which were complete. Maybe in experimenting with the sound they did try a couple by the back door of the studio. Emerick is very specific about this saying: “….there was a little spot outside the echo chamber with just enough room for [Paul] to sit on a stool. I ran a long mic lead out there and that’s where we recorded “Blackbird”. Most of the bird noises were dubbed on later from a sound effects record, but a couple of them were live, sparrows and finches singing outside the Abbey Road studio on a soft summer eve with Paul McCartney.”

That seems like a pretty detailed description. He doesn’t say that the reason the bird noises are on the track is purely because it was recorded at the back door. He acknowledges the actual blackbird birdsong is a sound effect added in later – but that there are some other natural bird sounds in there that were recorded at the time. It’s well known that the mono and stereo mixes of the song are different, especially in their use of the bird sound effects. If you listen closely to the mono mix you can hear some other birds in there apart from the blackbird sound effect recording. That I think gives added credibility to Emerick’s recollection.

As to Lennon not appearing at all on ‘Ob-La-Di-Ob-La-Da’, well that’s just not what is said in the book. Emerick makes it clear that John was involved in the recording. It was a song he detested, yes, and like the others he got heartily sick and tired of the number of times that Paul wanted to rehearse and record the song. It took days in the studio to get right, and in fact at one point Lennon did storm out of the studio – but he definitely played on it. See pages 246-248.

LikeLike

Well, I wasn’t there, that’s all I know ;-).

A further interesting read about the differences in opinion between Scott/Emerick: http://www.macca-central.com/news/2100/

Thnx for your splendid blog!

LikeLike

If you paid attention to the section on O-bla-di-O-bla-da you would have noticed that Emerick wrote that because John was tired of recording the song so much that he came in and took charge by recording the song with a few of his own changes. Emerick later said that they ended up using one of the takes from John’s session.

LikeLike

I was lucky enough to be at an audio industry event in Sydney several years ago which included a session with Geoff Emerick (and Richard Lush, Geoff’s assistant engineer), and I asked two questions: one was about the absence of Paul playing bass on ‘She Said, She Said’ after a reported disagreement, and the other was about the mixup that had the incorrect matrix version of side 2 of the mono Revolver briefly released and then recalled when it came out (it contained a noticeably different version of ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’). Neither of them had any recollection of either event, even though I would assume that each would have been fairly significant events at the time. It just goes to show that when you’re talking about things that happened in your working life some forty-odd years ago, you’re not always going to remember all the details!

As for ‘Ob-La-Di-Ob-La-Da’: if I’m not mistaken, things turned around when John came into the studio one morning and bashed out what we now know as the introduction to the song on the piano, after days of the band trying to get the song right. It changed the complexion of the song, and they then were able to knock it over fairly quickly.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Emerick was a personal hero of mine – but he didn’t do himself a favour with this book of “fairy tales”.

Ken Scott listet some of the worst mistakes, but why even bother to go into detail, when there are so many obviously made up stories?!

Emerick writes about 300 words about how John recorded “his” aaaaahs in “A day in the life” – although it’s obviously Paul on the record!

There’s no shame in being young and mostly high while working with the most important band ever, but it IS a shame to make up fairy tales about this time and sell them for fact.

LikeLike

Sorry, ….it’s John doing the “Ahhhhs”, with Paul mixed in the background …..of this I am sure …

LikeLike

Nope, you’re completely mistaken – although you’re definitely not alone in that mistake. There are youtube videos with the isolated vocals, and not only can you clearly hear Paul on the main voice but also John’s typical nasal high falsetto in the background.

There’s a lengthy articel about it on the website “The Beatles rarity” with all the needed proof. As you can see in the comments, not even THAT is going to prove some people the truth. But as long as you want to believe it’s John, that’s ok, it just doesn’t change the fact it is Paul.

http://www.thebeatlesrarity.com/2015/08/06/asknat-concerning-the-vocal-track-for-the-dream-sequence-in-a-day-in-the-life/

LikeLike

The aaaaaaah is definitely john..

LikeLike

No, you’re mistaken – but not alone in that mistake. See reply above.

LikeLike